Magic To Do

by George Heymont San Francisco-based arts critic

Over the years, acting has been hailed as a noble profession by some and equated with prostitution by others. Whether or not participants will get paid for their services is often in doubt. Yet there is no question that a wide variety of personalities benefit from participating in the art form.

- For shy people who prefer not to be in the spotlight, acting provides plenty of jobs for stagehands, tech workers, and other support staff.

- For people who thrive in team-oriented endeavors, acting can provide meaningful and challenging work.

- For raging egomaniacs with talent to spare, acting can satisfy a narcissist’s bottomless need for adoration.

While acting allows people (however briefly) to become someone other than themselves, it also provides a unique kind of therapy for introverts battling emotional securities. Many a performer will confess that, in their private lives, they are fairly quiet people. Famous opera singers like Leonie Rysanek often admitted that, without a costume to wear and a character to portray, they felt lost on a stage. And yet, for certain neophytes, acting can be a powerful portal to greater self confidence and awareness of those around them.

Two new documentaries show how acting affects different types of personalities. One focuses on an unusual group of Chinese students involved in a musical theatre project in Hong Kong. The other pays tribute to one of the greatest talents (and egos) in the history of film and theatre.

“Orson Welles was truly a magician, able to juggle complicated ideas and techniques (as well as a complicated life) to create the essence of art. A few things seem incontrovertible: that he was ahead of his audience, and even further ahead of his employers (one executive told Welles that the audience expected hamburgers, so no matter how good a dish he could make, better to just give them a hamburger). With Magician, we tried to show the power of Welles’s distinctive charm and provocative personality on screen and off, his life as a star, political figure, a fairly good magician, an aficionado of bullfighting, a lover of food, wine, the good life, and of many remarkable women, a man with a life of constant movement and exploration. Welles spent his life juggling art and commerce. Sometimes he behaved badly, selfishly and in many instances, against his own interests. Still, he was a fascinating personality with a remarkable life story and his films, in my opinion, are among the best there is in cinema.

We were committed to getting all of Welles’s finished films and as many of his unfinished films as possible into Magician. I had a wonderful couple of years working with and studying these films, which I had thought I knew. I realized that Welles, like Kubrick and Altman, created exceptional cinema that felt and looked like Hollywood films, but weren’t. Welles had a vision of his own, and a fantastic set of filmmaking skills. He was a strong writer, a great director of actors, an inventive visual artist, and a brilliant, innovative editor. He wasn’t without flaws, though, and I hope Magician shows that, too. He was not a great fundraiser, producer, or sufferer of fools. To tell this story, I was fortunate to have the participation of many members of the Welles community (scholars, associates, family, friends, even an enemy or two). At times they disagree with each other or with Welles. Whether Welles was one of the greatest filmmakers who ever lived (as many informed people feel) is something audiences can debate. That he was a singular filmmaking talent with a life that matched the singularity of his work was never in question.”

during one of his magic shows

Born in Kenosha, Wisconsin on May 6, 1915 (the day before the RMS Lusitania was torpedoed), Welles was deemed a musical prodigy at the age of 10, directed a Shakespearean play at 14, became a painter at 16, and (long before he started performing acts of prestidigitation) showed an early talent for kleptomania. He was a star of stage and radio by 20 and, at 25, co-wrote, produced, directed, and starred in his first film, Citizen Kane (1941).

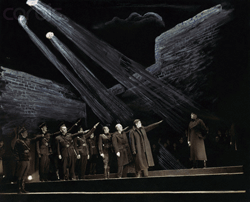

At the age of 20, Welles directed a production of Macbeth for the Federal Theatre Project’s Negro Theatre Unit, with music by Virgil Thomson. Set on a fictional Caribbean island (where Shakespeare’s witches were replaced with witch doctors), it became known as the Voodoo Macbeth soon after its premiere in 1936. In 1937, he directed Marc Blitzstein’s musical, The Cradle Will Rock, in a Federal Theatre Project production which became a legendary moment in theatrical history.

Shortly after co-founding the Mercury Theatre with John Houseman, Welles directed, produced, and starred in a famous production of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar which opened on November 11, 1937 when he was only 22 years old. After that, Welles made history (and scared the bejesus out of millions of Americans) with 1938’s legendaryWar of the Worlds radio broadcast about aliens landing on Earth.

During his Hollywood years, Welles often performed magic shows with his good friend, Marlene Dietrich, appearing as his assistant (an unfinished television special was named Orson Welles’ Magic Show). In later years, Welles became a familiar face on television talk shows and enjoyed making appearances in popular comedies. In 1975, he narrated a documentary entitled Bugs Bunny: Superstar.

One thing is certain: If you enjoyed 2008’s Me and Orson Welles (starring Christian McKay, Zac Efron, and Claire Danes), you’ll love Magician: The Astonishing Life & Work of Orson Welles. It’s the real thing. Here are the trailers for both films:

Some of the students Yang follows have problems which would not only prevent them from participating in musical theatre under normal circumstances, but whose situations could easily make them doubt the value of even attempting to enter such a program. However, Nick Ho (a teacher, playwright, and producer) is someone who firmly believes in the power of musical theater to transform a person’s life. Here are some of the students chosen to participate in his school production of The Awakening:

- Ho Yin Hui failed to get into one of Hong Kong’s top-tier secondary schools. Rather than deal with the shame he feels about having to repeat a year of classes, he prefers to act out, joke around, and cover his pain with a lot of good-natured mischief.

- Jason Chow is a good-looking, energetic teenager with lots of personality and a talent for getting into trouble with the authorities. Even though musical theatre has never appealed to him, his school principal hopes that getting Jason involved in a project that requires teamwork might give him a new perspective on life and instill some respect for his parents and teachers. A frequent smoker who has no problem cutting classes, Jason is one big challenge waiting to be solved.

worried whether he deserved to participate in the program.

- Sio Fan Lam may be blind, but she compensates for her lack of vision by working hard to prove to her peers that she is not disabled. After working with her, some of the sighted students in the program realize how much they get away with in comparison by slacking off just because they can.

- Tsz Nok Lin is a teenager who lost his vision a year before this project took place. Not only does he face challenges in learning how to act and sing with a group of sighted students, he is is struggling to find a way to tell his parents not to be ashamed of his disability. He wants them to understand that he’s going to be all right, and that he’s only lost his vision — not his life.

student named Tsz Nok Lin to help build his confidence

In her director’s note, Ruby Yang explains that:

“When L Plus H Creations Foundation decided to put on a musical, I proposed that they train a group of high school students who, through their own youthful perspectives, would film the whole process. Six student filmmakers were chosen to participate. Several months later, I went to observe the rehearsals for the musical. The first thing I spotted was music director Emily Chung coaching Tsz Nok (a student who had recently lost his vision) on his singing. With great effort he read the Braille using both hands. I could feel the strength and immense effort he put into singing and found it deeply affecting. After much deliberation, I finally decided to return to Hong Kong to direct the documentary.”

“The students chosen for the production were from disadvantaged secondary schools. I do not regard them differently from their higher-achieving peers, but question why this label of ‘low-performance’ has been forced upon them. During the course of filming My Voice, My Life I was with these young people on a daily basis. To a few students, I served as their counselor. By filming them, the camera became kind of a therapeutic tool. At the same time, I witnessed the personal growth that the musical training had given them. Strong bonds were being formed with the school principals and teachers.”

In 2010, a documentary about the Freddy Awards (written by Christopher Lockhart and directed by Matthew D. Kallis) focused on American high schools whose students were enthralled to be participating in musical theatre programs and competing against other schools in fully-staged productions of Broadway musicals. However, if one watched Most Valuable Players closely, it became obvious that most of the students in the film were from financially stable families (as opposed to some of the students in Yang’s documentary, whose parents work long hours just to be able to feed their children).

The students in these two documentaries differ widely in terms of financial comfort, burdens of shame and/or disability, and self-confidence. Without a doubt, watching the students in Hong Kong perform the Act I finale from Les Misérables brings a new and much deeper meaning to the moment. As filmmaker Ruby Yang notes:

“Although filming the documentary is over, this is just the beginning of a new chapter in the students’ lives. Whether they will take charge of their lives remains to be seen, but it is undeniable that the seeds of personal growth have been planted in their minds, waiting to bear fruit. For example, 16-year-old Jacky (one of the student filmmakers) struggled with dyslexia, poor reading ability, and found it difficult to express himself. During the course of filming My Voice, My Life, Jacky finally discovered his passions, learned new skills, and enrolled in video-making classes. 18-year-old Sau Yan Wong is a recent immigrant to Hong Kong who discovered her love of the stage during the filming process and applied to a film school in Taiwan. These are perfect examples of the impact one’s life can have on another: one’s own decision affects oneself, and also influences those around him or her.

For those working in the arts, there is never any doubt about the potential of a theatre program to have a profound impact on young minds. Compare the trailers for these two documentaries (you’ll probably have to watch the trailer for My Voice, My Life in full-screen mode in order to read the subtitles) and see if you notice what sets them apart.

Originally published at huffingtonpost.com