The unwilling blind teenage comedian “sees” more after losing his sight

by Melanie Leung

Lin Tsz-nok was on a roll. Everything he said cracked up the audience, and that’s how he won the secondary school category of Hong Kong’s second Thanksgiving Stand-up Comedy Competition, organised by the charity group Dreams Possible.

That’s quite an achievement for someone who lost his sight a few years ago because of a disease he inherited. Tsz-nok could be a poster boy for rolling with life’s punches, but here’s a surprise: he doesn’t like performing.

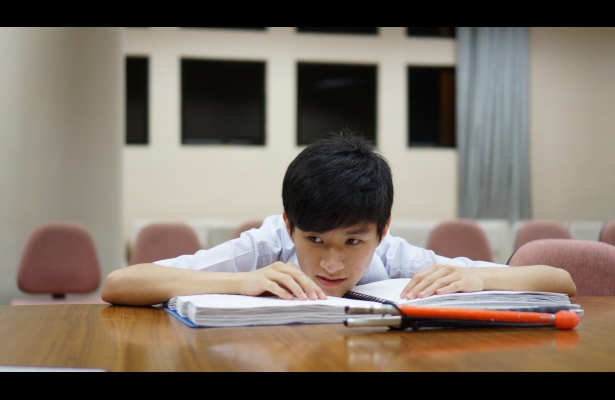

Photo: Melanie Leung

“[My comedy routine] is just silly. I didn’t know how it could make people laugh,” says the soft-spoken 17-year-old, who entered the competition at the insistence of his teacher at EbenezerSchool for the Visually Impaired, Ben Fong Tin-tai. “He told me he’d help and signed me up. The teachers here often think we lack opportunities, so they try to make up for it wherever they can. They thought I would like to perform.”

Tsz-nok was hardly enthusiastic about it at first, but he decided to give it a go. Not very confident of speaking in public, he spent countless lunch periods practising with Fong. When he finally took to the stage on October 26, the laughter made it all worth the effort.

“Mr Ben says he’s so handsome, many girls go up to him for directions,” Tsz-nok said in his routine. “But he can say anything he wants, and I can’t contradict him because I can’t see! Who knows, maybe the girls come up to us because I’m handsome!”

The routine is filled with funny stories about being blind, like one about friends plopping grimy fake eyeballs into his soup. Not all the anecdotes are true, but they serve to express his gratitude towards his grandmother and teacher for helping him cope with his blindness.

Tse-nok suffers from Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, an inherited form of vision loss. Two years ago, a white spot began to impair the vision of his left eye, which spread and destroyed his eyesight within seven months. The condition kills cells in the optic nerve, which transfers visual information from the retina to the brain via electrical impulses.

“If the doctors just shine their torches to inspect my eyes, they won’t see anything wrong,” explains Tsz-nok.

He says he’s not sad that he’s blind. “You don’t believe it, right? A lot of people don’t believe it. Probably because I always look sad,” Tsz-nok says. “I used to see blind people on the streets walking with a stick and I’d feel sorry for them, but [now I have to walk with one, and] it’s actually quite fun. And Braille is something other people don’t care to learn. But I did, so I’ve experienced more.

“Compared with people who were born blind, or those who just suddenly lost their vision, I’m really lucky.”

After he lost his eyesight, he transferred to EbenezerSchool and lived there two nights a week to learn Braille and other life skills. He was nervous at first. “Before I became blind, I didn’t even know the school existed. ‘Are the students retarded?’ I wondered. But on the first day, I heard them using slang and cursing, and I realised they’re normal people,” says Tsz-nok.

And as he got to know more people, he was amazed by how some of them made up for their blindness by using their other senses, some of which are remarkably acute.

“Some, who’ve been blind all their life, can play just by listening. Some of them can even tell which number bus is approaching by the sound of the engines.”

After two years at Ebenezer, Tsz-nok is back in Form Three at St Paul’s College. He says his friends there take good care of him. “They’re always afraid that I’ll get hurt, like I’m the handle-with-care type. It’s fine to get some bumps here and there; I’m not tofu,” says Tsz-nok, adding that he’s also learning to accept other people’s good intentions.

In some respects, he finds it hard to keep up with the class’ progress because he reads Braille more slowly, so he tries to catch up in the library while his classmates are in science class. He cannot take that class because he can’t conduct experiments.

Tsz-nok’s family, who like their privacy, are still reluctant to let people know about his blindness. When he goes out with them, he leaves his stick at home and holds their hands. “People just think I’ve injured my leg or that my grandmother isn’t well,” says Tsz-nok.

Last year in September, he shared his story with the audience after his performance in the musical The Awakening, the preparation of which was chronicled in Ruby Yang’s latest documentary My Voice, My Life. “After I became blind, I actually saw more. It’s abstract, but the circle that is my life has broadened,” says Tsz-nok, who met people from band three students to well-known businesspeople while doing the show.

“I’m still stiff about sharing my feelings, but I have to speak more because I now rely on sound. I’ve realised people don’t find my sharing boring, but they ask questions, or laugh. They can relate. That’s encouraging.”

It was past dinnertime, and the sky had grown dark. Untroubled, Tsz-nok made his way effortlessly to the canteen for a late-night supper, with the music of Alfred Hui in his ears.

Young Post Dec 4, 2014